Interview with Peter Greenaway conducted at the British Film Institute's offices in 1982. It became my first front cover story when it was published by Sweden's Chaplin magazine in 1983. I was struck by the film 'The Draughtsman's Contract' when I projected it at Chapter, a local art cinema in Cardiff. It was to become more than an arthouse movie thanks to its quality and for the backing provided by Channel 4.

Peter Greenaway

The original London poster for The Draughtsman's Contract

Set in England in 1694, The Draughtsman's Contract is the story of a landscape draughtsman, Mr Neville, who is seduced by both a mother, Mrs Herbert, and her daughter. The elaborate way in which the draughtsman is lured into the maze of intrigue they have created begins with a contract drawn up where in return for twelve drawings from Mr Neville, Mrs Herbert is obliged to make herself available for twelve sexual favours of his choosing.

The film started off as a British Film Institute (BFI) production but the costs became too high and Channel 4 - the new fourth television channel in Britain paid half of the £300,000 needed to complete the film.

In 15 years Peter Greenaway has made 24 films, some of them only 3 ½ minutes long up to The Falls his last film which lasts three hours. The early films were all personally financed and it was only in the late 'Seventies that he started getting public money, grants from such bodies as the BFI (a body which receives money from central government to fund independent films. The films are not meant to be profit-making and so allow a fair amount of freedom to the maker). Virtually all his films before The Draughtsman's Contract were inaccessible to the majority of the commercial and cinema-going public. The obvious question to ask after such a long period making films that were evidently personal and beyond most viewers' comprehension was:

Why the sudden change to the more obvious narrative format of The Draughtsman's Contract?

GREENAWAY:- Any film maker who says that he's not interested in his audience I'm sure is lying. A film is not a film if it's in a film can. A film is not a film unless it's on a screen. Almost inevitably what was important as far as I was concerned was that this audience should grow larger and larger.

The scheme and ideas I had had became more ambitious, they needed more money and I was very fortunate in having support from the BFI mainly in the person of Peter Sainsbury, who is the Head of Production there, who has followed my work ever since he met me way back in the early 'Seventies. He encouraged me to go on, pushing forward my private concerns, my interest in systemics, structuralism, and formalism, concerns that were around at that time along with concepts of land-art and general conceptualism. All things which could not be called part of the public domain in cinema but nonetheless had a following from people who were as much interested in painting as they were in films.

So I made these films and was grateful to see that the audience got a little bigger each time these films were shown. I began to be noticed by the more conventional media and a producer from the independent television network encouraged me to make a film for them. It sounds a little astonishing that a major television channel should support an 'avant-garde' film-maker, so-called. I made a film called Act of God which was to create a pattern of circumstance out of basically material which denied classification. It was a half-hour film which showed actual lightning victims with fictional stories linking each one. It was for me a question of how you can classify those people struck by lightning and it was over that whole dichotomy that the film was based.

That was shown very late on a Monday night and almost in one leap the audience that was interested in the kind of films that I make jumped a hundredfold. And then I was encouraged to put forward more ambitious, more outside-the-closet films like The Draughtsman's Contract we've just completed. Now I find there's only been a few public showings of this movie, enormous interest and the small audience I had before has grown really enormously, it has increased by a thousandfold.

As The Draughtsman's Contract reaches its European audience, would you prefer that the film be dubbed or sub-titled?

Page from Chaplin article on Draughtsman's Contract

GREENAWAY:- In Italy where the film is ready to be distributed it is going to be dubbed, they already have the actors to do the voices. I would hope that in other countries The Draughtsman's Contract was subtitled rather than dubbed, because the whole concern with language has been a prerequisite of all the other movies I have made. I'm interested in double-meanings, double-entendres, puns, word-play, word-inflection, word-nuances and so on. I'm a very English film-maker, interested in language and intending to stay that way.

I make no apology for that it's just the way I want to make films, I would rather have dialogue anytime over special-effects which seems to be the inevitable way that the cinema seems to be going at the moment. Also I'm happy enough not to have been born a Pole, or a Finn or an Estonian. I do belong to a majority language.

There is a problem that is almost never resolved in period films, the external world, the skies, clouds, trees, and so on, seem alien to the props and setting installed around them. It doesn't seem to matter whether the actors and actresses are in period costume or not because when they on horseback, for example, feels modern. What problems did you have in getting the setting and reactions of the players right?

GREENAWAY:- First of all, let me say that I was surprised that the BFI with its modest budget would be prepared to take on a costume-drama in the first place. With a three-dimensional costume-drama the price of the piece shoots up if you're going to do anything of any credibility. Second, we had some really excellent talent from people that had worked at large in the commercial movie industry, especially Sue Blane who did the costumes and Bob Ringwood who did all the set-design.

Then an amazing chance came our way when we found the 17th century house that we needed in the south of England. Privately owned, built in 1660, it was filled from top to bottom with the correct artefacts of the period. An extraordinary godsend to us because it just set the scene, the scene was there already. All we had to do was hide the television aerial, hide the burglar alarms, put some new gates on, cover up one or two other 20th century anachronisms and we were off.

Did the fact that you nearly ran out of money limit the effects or cut any of the scenes you wanted to do?

Page showing Anthony Higgins, from the Greenaway article in Chaplin magazine, Nov 1983

GREENAWAY:- No it didn't. We had quite a full script and all those scenes are very carefully organised and preordained in a sense, much as I hate making paper films I'd rather make things as they happen. I did re-write scenes slightly as we found sheep on the premises and other minor incidents but it's funny that of all the scenes that were re-written only two were ever used.

We have an enormous amount of material that never went in. The first cut of the film we made was three hours long. It was a cut that I enjoyed very much because it was more like a large documentary slice of late 17th century England rather than a sort of cryptic Borgesian thriller. But after having made The Falls a three-hour-plus move, there was no way that anybody was going to let me make a three hour movie again.

What impression has Borges left with you?

GREENAWAY:- Ever since I discovered Jorges Louis Borges in the early 'Sixties he's certainly been for me an amazing writer and influence. Everything he does I read avidly. The other literary influence is Calvino who has connections with Borges. The thing that I like about Borges is that he would never write something as lengthy as War and Peace. He'd write a synopsis of it and present it to you in three pages.

The Falls is full of those sort of Borgesian ideas. The film consists of 92 biographies of people who all have some connections with one another apart from the fact that all their surnames begin with the letters FALL. They've all been picked out of a dictionary and each is explained in his relationship to birds, the orthonological phenomenon in its widest possible sense. Regarding flight as like the last frontier and I don't think flight has been adequately covered by Concorde or helicopters, we still need to take-off personally and all the metaphorical implications of that as well.

The English are the most avid-bird-watchers in the world, so there's a whole sort of anti-English critique involved in the movie as well. And it's full of anecdotes and conundrums and life histories and whimsies and impossible stories and so on which are all bound together to represent a compendium, 92 different ways of making films. Each person also speaks a different language, there are 92 fictitious languages in this world.

Are you more interested in writers than in cineastes?

GREENAWAY: - I'm more interested with writers and painters rather than film-makers, yes. That would be true of the last 10 years, it may not be true a little bit earlier. I did all my formative film-making in the late 'Sixties and early 'Seventies. Nouvelle Vague was around at that time, Antonioni, Passolini were the heroes, but ever since the mid-Seventies I've gradually ceased going to the cinema, I'm much more interested in literature and in painting.

If you'd been given double the amount of money how would the film have changed?

Front cover of Chaplin magazine, issue 5, 1983

GREENAWAY:- I had no conception originally that the film would look as rich as it does. Let me make two comments; in Kaleidoscope film magazine it was suggested that the film looked production-wise as good as Barry Lyndon, and I emphasise production-wise; The Times reckoned it looked as if it had cost 10 times as much, that is £3 million. And with comments like that we do have a film that does look extraordinarily good and I wonder if we had doubled our budget whether it could have looked any better.

We cut lots of corners. We shot it on Super 16, which probably saved us about £30,000 on stock and time and processing. The mobility of the 16mm camera as opposed to the 35mm probably saved us four or five days. If you work that out in cost times we reckon we saved about £35,000 on that. It also put on the line the efficacy of Super 16 and because of the critical reaction we no longer have any fear about that. Most people don't even know if it was shot on Super 16, the production results were so good.

As well as this, all the crew and cast from Janet Suzman - the leading actress - down to second-grip earned the same amount of money, they worked 17 hours a day, seven days a week for seven weeks, and I'm deeply indebted to their enthusiasm, commitment and belief in the film.

How important is music in your films?

GREENAWAY:- It's very important, partly because I've known Michael Nyman now for 14 or 15 years and most of the films I've ever done have been alongside him. I'm interested in musical structures, I'm interested in what music does. He and I have an ongoing dialect about the whole problem. We've taken films and live music around the country on tours, to try and demonstrate to the public the relationship of music on film.

This is an old argument that goes right back to the early piano players in the cinema, it goes back to the relationships between people like Eisenstein and Prokoviev. Basically music is always regarded as secondary in film and film-making, and we're anxious to give it a more equal status. I just thoroughly enjoy using music. I can do most other things in making films, but I can't write music. Maybe if I could write music, I'd do that as well.

This is the first time you've used actors in a film. Actors are obviously important in theatre but in films their voices can be changed in the editing stage and their acting construed in a totally different way to how they originally acted them. How do you see actors and acting on film?

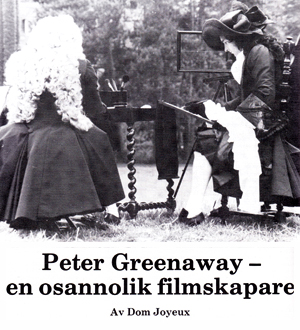

Still showing the Draughtsman's Contract being drawn up - Janet Suzman (left) and Anthony Higgins (right)

GREENAWAY:- Well I approached this film with a certain amount of apprehension. Both on an aesthetic ground, I kept on asking myself "What the hell am I doing with actors? I've never used them before, do I need them?" And secondly because I know very little about the theatre I was very chary about how we would get on. I realised that a lot of my ideas were not conventional, that they were interested in things like close-ups for example because of all their problems being actors, they were interested in dialogue-delivery, they were interested in action. Comparatively speaking there's very little action as such in The Draughtsman's Contract except perhaps on two occasions.

So, it was necessary when we did the auditions to find actors who had a theatrical experience because some of the sequences are very very long and in the three-hour version some of the takes lasted eight minutes. So we were keen to find people who were disciplined in the theatre who could stand and hold-up an emotional scene for a long time, not to rush on, say three lines and rush off again. That was the reason for choosing Janet Suzman and probably Anthony Higgins.

After some initial teething problems, we all gradually began to see eye-to-eye. One of the points we made early on was that it was essentially a cast and crew production, they gave a hell of a lot of their discipline and their experience into my inexperience in those particular areas. I've had some extraordinary compliments about the acting which really surprised me because my experience with acting is extraordinarily minute.

For your next project you are thinking of doing a film on Inigo Jones, the 16th century architect…

GREENAWAY:- That is only one project, there are in fact about eight projects around in various forms. And what has happened now is that I've shelved that one until some other time because I realise it does need an enormous budget to be made well and maybe it would be nice to think that if my film career continues, it might be the film that I make money with in five to six years time. I also think that it would be politically unacceptable for me to make another period movie directly afterwards because I'm going to get type-cast as a guy who can only make period movies. The next film is called Drowning by Numbers and is a contemporary drama set in Yorkshire.

I was going to say, that by placing the story and characters of The Draughtsman's Contract in the past, you are able to include sexual degradation and noblesse extravagance much more casually than if the film had been set in a modern-day context.

GREENAWAY:- I think that the ideas that are existing in The Draughtsman's Contract and the problems considered in the film are as relevant now as they were then. It's about human relationships, lust versus avarice, all those English problems of being outside and inside themselves, they're all there.

A character that is featured often in earlier films, and is sometimes considered your alter-ego, is Tulse Luper. Has everything that there is to be said Mr Luper been said?

GREENAWAY:- No. There's another film coming up about Tulse Luper, called the Tulse Luper Suitcase which examines the man through 4,001 artefacts found in an abandoned suitcase in a railway station and the other one is called The Bathroom Arrest when Tulse Luper is put in prison for false ecological crimes and it's about how a man copes with artificial imprisonment because he happens to be imprisoned in a bathroom on Brussels railway station.

Who is the person what interests you most in modern or latter-day cinema?

GREENAWAY:- If you'd asked me 10 years ago I would have said certainly my favourite director was Alain Resnais, probably Marianbad is the apogee of film-making. I have not seen Marianbad for about five years now and I need to renew this opinion every now and then. But in terms of literature, and I think that literature is at the forefront of ideas and some senses film drags on behind, certainly Calvino and Borges. But what's tending to happen now is that I'm reading literature of a much earlier period, someone like Laurence Sterne for me is absolutely amazing. If ever I could have written something like Tristram Shandy I would think that would be the peak I could reach.

I would rather go to see an art exhibition of a painter I admired like Kitaj for example if he were to have an exhibition in Rome, I would go that far. I also have a very large library of contemporary literature and I buy books like most people eat cornflakes.

In The Draughtsman's Contract the camera is always static. Why?

A still showing the dimension of the 'grid' size used in the movie The Draughtsman's Contract © BFI

GREENAWAY:- A facetious answer first of all. In some ways all the pictorial compositions are based on paintings, paintings don't move. Second, if anything it's a reaction to the camera movement of most contemporary films which behaves like somebody with St Vitus' Dance, they never sit still. Also, there is the examination of picture ratios which I was interested in like de la Tour, Poussin and Claude, who use the same ratio as the one I've chosen. It's the fixed arch, the fixed frame and within the film there's talk about 'the grid' which again is a fixed ratio which is the same as the ratio of the film. Since the whole film is about representation, I'm very keen to keep film frame absolutely static. I like the idea of characters choreographed within a chosen fixed space.

Did this cause any problems, your insistence on having the camera absolutely still. For example, the comic shot where a naked mobile statue appears on top of the roof after the camera has been concentrating on the people feasting on the table below. Perhaps the normal cameraman's reflex would have been to pan out to include the roof.

GREENAWAY:- I resisted that, I don't want you to get me wrong because the relationship between me and the cameraman was extraordinarily good. But there was this sensation, the cameraman wanted to do just as you described. On the one hand the actors were always asking for close-ups and there are very few close-ups in the film and the cameraman said if we open up a bit or we move the camera that way nobody will ever notice. But I was absolutely insistent until it became a standing joke, that people said "For Chrissakes, don't move that camera or the movie will collapse!" Having said that there are certain camera movements but they're very static ones, they're very non-organic movements.

That particular size frame, how will that be affected on television?

GREENAWAY:- That's a problem. What's going to happen is that we're going to have to mask it so in fact we get the ratio and have a black line on top and bottom. I must insist on that because the compositions are worked out so carefully to the frame. It's the painter's eye, a painter would be prepared to take the subject to the edge of the frame.

How long can you keep the film away from television because Channel 4 have the option to show the film whenever they like.

GREENAWAY:- It is at present being debated. It is to our advantage to keep it off the television as long as possible. It is also television's advantage to keep it off as long as possible. Because there is still the kudos of the cinema going on television. If the film can get a reputation outside it means that more people will watch it when it does go out on the small screen.

My say in that decision will be small. It is probable that Channel 4 will want to put it on in the spring or autumn, not in the summer when television audiences go down. But the longer the delay, the better as far as I am concerned, we must have a big theatrical release and that's going very well at the moment. It had a standing ovation for three minutes at the Venice Film Festival, made a good impression in America and has been sold to European countries including Sweden, Denmark, Italy and West Germany.

© Dominique Joyeux

Draughtsman's Contract trailer

Want to buy the movie?

According to this Peter Greenaway website, the director watches The Draughtsman's Contract once a year, by himself, at the same time and on the same date.

Everything else you could possibly want to know about The Draughtsman's Contract.

Published in:

Chaplin magazine, issue 5 for 1983. I don't think that the Swedish film magazine Chaplin exists any more. It's a shame as they had a nice design feel to them, paid well and Lars Ahlander was a really encouraging editor. Chaplin usually printed my articles without changes - I say that not being able to speak Swedish but I can track key words and they really didn't seem to alter much. They selected good images and went the extra mile in layout terms