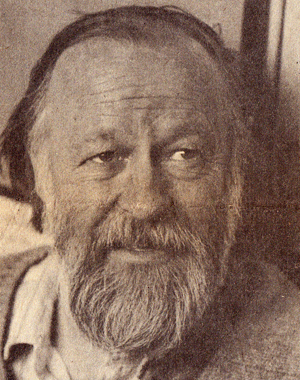

I conducted two interviews in 1985 with the director of the National Film and Television School. I like the subhead that came above the headline in the Indian useage of this interview 'Teaching - an Art'. Professor Colin Young does look like a kindly academic but he had his feet firmly planted in the real world. He was such an inspiration to a generation of British filmmakers - check out the alumni to the school when he was in charge (at the foot of this page) they include Nick Park and David Yates. This interview was published by a variety of publications including a Bollywood paper (above), a university journal and, of course, trusty Cahiers du Cinema.

Colin Young

Britain was one of the last, if not the last, European nation to decide that it wanted a National Film School. In 1965, a committee of wise men from the British film industry and the British government toured and inspected five European film schools. In 1970, fifty years after the Soviet Union had created its school, Britain established a National Film School at Beaconsfield, 20 miles north-east of London.

The school's first director had to be somebody who could command the respect of a sceptical British film industry, Professor Colin Young, Chairman of the Department of Theatre Arts at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) was chosen for that reason. From 1964 to1970 he presided over what has been called the 'golden period' of UCLA. A time when various alumni passed through the school, James Morrison and Ray Manzarak who were the first, Francis Coppola, John Milius, Barry Levinson, Lawrence Kasdan and Arthur Marshall all attended UCLA in the Sixties. It was hoped that Professor Young would produce a similar successful formula in Britain.

Colin Young had left his native Scotland in 1952, heading for New York on a boat that took six days to cross the Atlantic. At the age of 25 Colin Young had graduated from the University of St. Andrews in Philosophy and was due to continue his studies at the University of Michigan. However, those six days on the boat gave him time to reconsider a future life as an academician. He reflected on his time as a film critic for an Aberdeen newspaper and a series of coincidences on arriving in New York led him to stay with friends in Los Angeles. By this time penniless but with a purpose, he became a gardener in order to earn sufficient money to become a student at the UCLA film department.

Young graduated and working as a technician he made his way up through various departments in the industry until he was commissioned to make short children's programmes for NBC and was eventually asked to return to UCLA as a teacher for six months. These six months were extended until 1964 when he was put in charge of the Californian Film School, a school which, like its European counterparts, Young found regularly under attack as to what purpose it should serve and indeed whether it should exist at all.

Raison d'être

Professor Young says: "Left to itself, no film industry would say that it really needed a school. That would be true in France with IDHEC and is probably true in all the so-called capitalist countries. People in a free enterprise system think that the market-place left to itself will look after everything and provide all the resources that are needed.

"It's an attitude that I have encountered while growing up in Scotland and continued to find years later among the politicians I met in California (including Californian Senator Ronald Regan) and which still survives in the film industry today. This attitude presumes that there is something the matter with somebody who has to go to school to make his way in life, that it is a sure sign of weakness in an individual if he has to go to school to learn how to do what he would learn in the workplace anyway.

"But there is a difference in attitude and technique between a person who has qualified through the industry and one who has gone through school. The person who has learned in the industrial environment entirely, will have his or her time directed by others in a workplace which is keyed to a production of artefacts of somebody else's requirements. The other type will have their time directed by themselves in a school environment which is keyed to their development and will leave within them a spirit of an inner-directed development as opposed to the industry's outer-directed one.

Self direction

Photo of Professor Colin Young published by Screen, India 1987

"It is only in an environment like this that the next generation will have a chance to think about their future in a systematic way. At a film school the students are given the courage of their own convictions and they are given time in which to achieve that. The chance to practice with film and get it wrong, again and again, until they eventually get it right. They need this opportunity to test themselves before they plunge into a market place which hasn't a reputation for being benign and which today is shrinking in the area of film production," says Young.

The buildings which the British National Film and Television School now occupies were originally built in 1927 as studios for the Crown Film Unit of Grierson's day. They became empty in the 1950s as the popularity for British films waned and the school moved in their cameras and offices in the summer of 1971.

The school, has been funded till now in the largest part by the government's Arts Department and by the Eady Levy (monies accruing to the various segments of the film industry from a levy on box office receipts). However, it is quite likely that the tax on seats - the Eady Levy - will be abolished this year or next. That means that voluntary contributions will have to be looked for and Professor Young is not sure whether this will be readily forthcoming.

When the first generation of film students had come out of the School in 1974, there was almost a feeling among the students that they had to pretend that they'd been in jail in the intervening period rather than film school. The school had no reputation, no status and no credibility. Today, ten years after, this climate has changed.

School's alumni

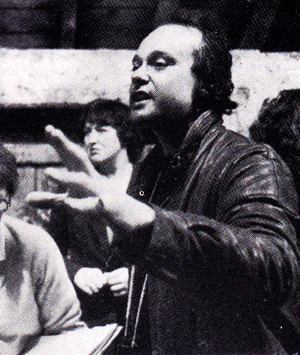

Michael Radford had made 'Another Time, Another Place' and '1984', Bill Forsyth 'Gregory's Girl' and 'Local Hero'. Julian Temple has made the successful cult movies ' The Sex Pistol's Great Rock 'n' Roll' and 'Absolute Beginners' and Nick Bloomfield 'Soldier Girls'. Jana Boková has made a huge collection of documentaries for British television and had a retrospective of her work in Rotterdam, two years after she had graduated. Now the attitude towards the school has changed.

Photo of Michael Radford taken from Z magazine issue 4 1985

Now, the same people in the industry who used to say to Young and his staff: "You are misguided out there in Beaconsfield. There is nothing extra that people can learn in a school" are saying that: "Graduates have an unfair advantage over other people trying to make films because they are an elite that have been given special privileges and treatment." The latter judgment is probably nearer the mark than the earlier expectation that nothing could be learned at the school.

The National Film School receives several thousand requests for joining the school each year. The number who persevere and put together a completed application with a portfolio of their films, tapes, scripts and photographs is considerably less. This year on January 31, the closing date for applications, the number of candidates totalled 444. The most promising of these candidates will expect to go through three interviews before finding out if they are to be one of the 37 students accepted for the next school year.

A third of the applicants are foreign, of whom the School accepts a fifth. This 20% acceptance of foreign students is to provide a mix at the school both for the cultural additions that they represent and for the different way in which they view films and the cinema. Of the students who will be enrolled this year, it is intended that three will be accepted in each of the categories of animation, editing and sound, that four people will study script-writing and six pupils will be accepted in each of the fields of direction, camera, documentary and production of film. In addition there are courses for those already in the industry. Last year, those people attending re-training programmes at the school numbered 200 in addition to those enrolled in the full-time courses.

During its first year, the National Film School had only one woman student out of the twenty-five persons enrolled there. Today, a third of its student population is formed by women, reflecting more or less the number of applications received by the school. However, in a business which prides itself in the relaxed attitude it shows towards gays, the politically radical, Blacks and the Jews there is a noticeable statistical bias against the acceptance of women in their ranks.

Talent shines through

Colin Young see this discrepancy and views it thus: "We have been graduating extremely well qualified young women as directors since the earliest days and only one of them at present consistently works as a director of fictional material and that is on television. I would say that there are half a dozen thoroughly prepared and competent women who could become top-notch directors, if the film and television industry would believe it.

"Some of these women say that companies don't take them seriously and don't trust them with money for projects that they are in charge of. Others say maybe women lack the killer instinct that men seem to have, the aggressiveness, the cold-bloodedness to go after something. They think that, for women, film-making is not their first priority - a value or an attitude towards living is more important. That a woman wouldn't make the same compromises that a man would make. Whatever the reason, it's a pretty scandalous outcome.

"When we graduated our first camerawoman Diane Tammes in 1975, she was the first camerawoman in British history, some eighty years after the motion picture camera was first introduced in Britain.

"Diane Tammes had shot a lot of film before she was able to make a breakthrough into the industry. She got her first break in a film for London Weekend Television based in a hospital where the patients were all women and a male cameraman was not allowed. Then on the basis of that assignment - perhaps leaving out a stage or two - she was assigned to an all-women crew to shoot in Marrakesh. For a long time it seemed that Diane was alright as long as an all-women crew was needed. Finally, she was able to make people realise that the relevant point was not that she was a woman, but that she was good. It seems just as hard for women as directors to make the same point and as long as women are not making half the films, we're missing out on half of life," says Young.

It is always difficult to decide how to measure whether or not a project has been a success; even more so when it is education that is in question. A return on financial investment is not really applicable to a school. Nor is the winning of prizes a sure measure of success, as there are many influences that bias a judge towards or away from a film, that are beyond the control of the film-makers. But if increasing the capability, the confidence and the imagination of an individual are signs of success, then the National Film School at Beaconsfield seems to have found a particularly effective formula for its students.

The School is helped by the experiences of its Board of Governors. Amongst them are Alan Parker, David Puttnam and Jack Gold who hold occasional seminars for the students. Among their teaching staff, giving workshops on lighting, script-writing and direction, they count Ossie Morris (Oscar for Fiddler on the Roof), Nick Roeg (director of The Man Who Fell to Earth) and Michael Radford (1984 with John Hurt in the leading role of Winston Smith). Young insists that the students are not made to feel awed in the presence of their illustrious tutors.

Photo of Sue Gibson taken from Womenbehindthecamera.com

"There is not the view as there is in other European schools, that the inherited wisdom the elder generation contains must somehow or other be applied on some contractual basis to the next generation. Here we are in the business of power-sharing. Because our own analysis is not that we know less than our European counterparts - because I don't think we do - but our belief is that our graduates will have to make their own way after the School and that they will be entering a world that has neither the prospect of long-term nor permanent employment," said Young.

Creative Teaching

James Blue provided the students at Beaconsfield with a fascinating example of creative teaching shortly before he died. James Blue had attended the French Film School in Paris and was film-maker, teacher and writer until he died in 1980 of a cancer that could neither be traced nor treated. He was given an assignment at Beaconsfield to demystify the job of direction. To demonstrate this he chose to screen for his students Karel Reisz's 'Dog Soldiers' with one scene missing - the one in which Nick Nolte arrives at Tuesday Weld's house to deliver two kilos of heroin and finds her totally unprepared. It is a key scene in the movie and Colin Young remembers the exercise as a highlight of the School's history.

Photo of Karel Reisz taken from Z magazine

"The idea was to see how well people can read a script and understand the function of any particular scene in it. They knew how the Tuesday Weld and Nick Nolte characters behaved and it was the students' task, working in five different groups, to cast the scene and shoot it as they thought it could best be fitted into Reisz's film. Each of the groups was given a day (Reisz actually had two days) throughout the workshop week to film and edit the scene on video tape.

"By Saturday morning there were five different versions, Karel Reisz screened each of the versions and analysed them as a sequence that would go into his film. He found points in them that had not occurred to him as a director. But there were also faults with all of them as a scene that would fit as a building-block to Reisz's film.

"Then we ran his sequence and he was perspiring with fear. He was hoping his sequence would stand up to criticism, having been articulate with what had been wrong with everybody else's. His was, however, the best version.

"There then ensued a discussion with Reisz of the differences. This was video-taped by the students in the groups and exists even today. It is the most extraordinarily concrete discussion between a director and students that I have ever witnessed. Beaconsfield students are not prone to play the tourist visiting celebrities, but this discussion was different. They had risked what Reisz had, and the discussion was from the inside. Blue's role in it was how a teacher's should be, that of an enabler, the insistent but friendly guide."

Young is regarded by his students as a kind of benevolent godfather. One who is always accessible on first-name terms to all and ready to share with them his infectious laughter. He makes the time to lecture in French at the CNRS (Centre National de Recherche Scientifique) in Paris on three of his passions, Ethnography, Anthropology and Film. He is also on various national and international committees on film. After 13 years as head of the National Film School, Young does not yet see his job at Beaconsfield as complete. "My job would be finished when I get bored with it. Then I should get out. I'm not bored with it, I'm just as amused by it as I ever was. The world out there is changing all the time."

© Dominique Joyeux

Postscript: The National Film and Television School is still thriving. Nick Park, David Yates and Roger Deakins have also studied at the NFTS in Beaconsfield. A fuller list of its alumni is here. The picture of Sue Gibson was taken from Womenbehindthecamera website. The first of many women to graduate from the NFTS's cinematography course, Sue Gibson is now one of the UK's leading female directors of photography. In July 2008, Sue became the first woman President of The British Society of Cinematographers (BSC), having broken the barrier in 1992 to become the first ever woman to be made a full member of the BSC.

Interview published in:

Norwegian magazine 'Z' (issue 4, 1985)

"We are a rather small magazine run entirely on idealistic grounds, and have no opportunity to pay any of our contributors. If you can accept this condition we would like to print your articles in the June issue...." Filmtidsskrift

Cahiers du Cinema, Novembre 1984. A nice double page spread in Cahiers' LeJournaldes section. I was so chuffed when Cahiers first published me. They translated me, paid me okay and made me feel welcome whenever I popped into their Paris offices - thank you Claudine Pacqout . They would never though, commission me. The deal was that I would not publish anything Cahiers published anywhere else in French, but was otherwise free to publish my articles in other languages.

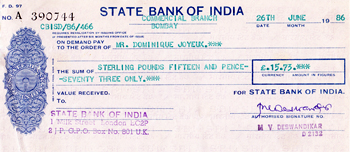

Surprisingly Screen, the biggest selling weekly paper in India at the time, picked up on this and printed it large. Their centre page poster spread measured nearly a metre wide and I took up a few columns in their April 1987 edition. I liked their cheque (from a previous article on David Puttnam) so much I kept it (there was no such thing as colour photocopying nor scanning in those days). I didn't cash it in and I've been told that that means the bank gained on this one as the money would have already come out of India Express Newspaper's account to generate the cheque. I love the effort that's gone into creating it, the embossed stamp, the watermarked paper, the tickertape print of the green ink and the fully written out signature of MV Deswandikar. It's a fully serious and ornate document of payment.

The German academic magazine Film-Kunst reproduced this in their Dezember 1985 edition