This is as about niche as you can get. An obscure topic for a little known magazine. Having said that, City Limits magazine, though no longer functioning, was a good leftie listings rival to London's Time Out during the 'Eighties. Here's the article as it appeared in the issue Feb 24 to March 1 1983:

Yiddish Cinema

Three hundred virtually forgotten films in the Yiddish language have been distilled by Australian-born writer/director Russ Karel into a remarkable new movie, Almonds and Raisins. Dominique Joyeux investigates this cinematic homage to a dying language.

With nearly two million immigrants, New York in the 1920s had become the largest Jewish city in the world. They spoke Yiddish, read Yiddish and sought Yiddish entertainment, so when the talking motion picture arrived in 1927 with The Jazz Singer, there was a large market for Yiddish films. Jewish entrepreneurs in New York set about making such films, at first with B movie-style low budgets but then on a larger scale.

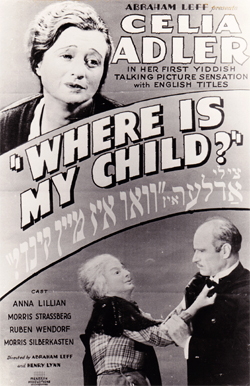

Film poster used in publicity for Almonds and Raisins

The stories tended to be inversions of the American Dream. As Russ Karel puts it, "Yiddish movies, instead of telling stories about prosperity, about making it, about the American way, started to tell stories leaning more towards the Moseaic tradition. From 1927 to 1939 there was a drive to show stories that were true to the immigrant experience. Sweatshop labour, strikes, strike-breakers, tales of despair, tales of broken families, fathers who spent 20 years on pushcarts selling garments, couples locked away behind counters in delicatessens."

Karel continues; "For the first two generations of 20th century Jews in America, it was a troubled time. When Roosevelt finally came along with the New Deal in the 1930s, they used to say in Yiddish "Dos Velt, Yenne Velt, Roosevelt", which meant "This world, that world, and Roosevelt". It was Roosevelt who allowed Jews, blacks, Hispanics an entry into the educational system where they could become social workers and government officers. Before him the number of Jews that had risen high in the state structure of American politics could be counted on one hand and it wasn't till after World War Two this trend would be reversed."

How did Karel set about making Almonds and Raisins? "It wasn't a straight-forward matter like the previous pictures I have made. Forgetting how difficult it was to get the footage, it's very hard to structure seven and a half miles of film. For that reason it was good to work in hand with Wolf Mankowitz who did the treatment for the film, aiming for a line of thought that was clear and succinct and would entertain an audience."

The Yiddish films of the 1930s set out to entertain their audiences by making them happy, by giving them what they related to. One movie starts with a father who is struck on the head by a strike-breaker and ends up in hospital with a temporary loss of memory. His penniless wife can't cope, sells her child for adoption, then kills herself in grief.

The father, when he gets out of hospital spends years tracking down his son until he finally chances upon the family that adopted the child. He then discovers that the family is being blackmailed by the child-trader who sold his son to them. He shoots the child-trader and sits in jail with a long prison sentence facing him. The coincidences continue as the son, who has since become a lawyer, is chosen to defend his real father without appreciating his true identity and skilfully dismisses the charges proffered. At the end the two fathers agree it is unnecessary to tell the son of his confused past and the film ends on a wave of tears.

The reunification and happy ending, typical of Yiddish films, was a comfort and signal of hope to those who were the victims of the destruction of European Jewry, the destruction that from the 1880s scattered and divided families to all parts of the world.

City Limits front cover Feb 24, 1983

The Yiddish film industry was, however, short-lived, its demise provoked by three concurrent episodes in Jewish history. The American Jews who by 1940 were numbering four million, lost their Yiddish through assimilation. Then with the establishment of Israel in1948, it was Hebrew that was chosen as the language for the new state. And by 1945, Europe was decimated.

Now there are perhaps 300,000 speakers left in the world, when in the 1920s there were some 12 million with the language. Today there are no Yiddish films made anymore, and Russ Karel's film is a testament to those that were.

The film is not for academics or film-buffs insists Karel and his co-producer David Elstein. "It's for entertaining. What films are about is putting bums on seats. We've spent a lot of money and even got Orson Welles narrating it. You owe it to yourself to get it seen by as many people as possible and you owe it to your financiers to get you money back."

© Dominique Joyeux/City Limits