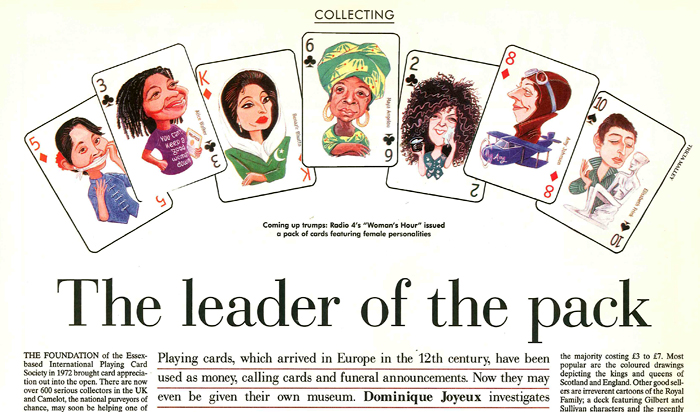

From the Independent on Sunday collecting section published 17 November 1996

Playing cards, which arrived in Europe in the 12th century, have been used as money, calling cards and funeral announcements. Now they may even be given their own museum. Dominique Joyeux investigates

Collecting playing cards

The Foundation of the Essex-based International Playing Card Society in 1972 brought card appreciation out into the open. There are now over 600 serious collectors in the UK and Camelot, the national purveyors of chance, may soon be helping one of them establish Britain's first playing-card museum: John Gosling has offered to put on display his large and varied collection in a redundant brewery next to Lewes Castle in Sussex.

The museum will give a general history of paper making and the origins of playing cards, as well as giving people the opportunity to learn how to play card games on interactive data bases. The irony is not lost on John that for a century Nintendo was a playing-card manufacturer, before it threw its hand in and began concentrating on producing computer games.

John, and his wife Sara, run a whole-food company, making and supplying soya-bean products. He was 52 and had been a jazz-record collector when he came across some old French packs in the bottom of a trunk in a junk shop: "I'd never considered collecting playing cards before because all the packs looked the same. When I saw these ornately designed cards, I was just bowled over. I couldn't believe that things of such delicacy could be used for playing games."

Most people are used to the standard English pack which has featured the same four suits, bearded kings and one-eyed jacks for 300 years. It is this pack that is used for playing international games like bridge, poker and whist.

What most enthusiasts collect, however, are the non-standard packs that have different court, and sometimes decorative 'pip' cards [all cards apart from the ace and the royals]. People also seek out the foreign cards with different suits whose packs may contain only 32 cards for skat in Germany, or as many as 120 cards for Indian whist-type games. There are collectors of tarot cards and of "transformation packs" where artists have incorporated the shapes of the suit signs on the pip cards into original and unusual designs.

John's collection, waiting for the museum's opening, lies in 100 drawers and line a dozen shelves at his family's 16th century home in Lewes. Although it's an eclectic collection, John specialises in the vivid, hand-painted playing cards of India.

"For cosmic reasons, Indian cards are round. The paintings generally depict aspects of the Mogul court or the 10 incarnations of Vishnu. Indians play with them while squatting on the ground, with cards laid out on a cloth and, when playing the Vishnu version, a form of mantra is said when laying down the card, thereby honouring the name of the God that is played. These games are not gambling games, rather they are used to test the players' powers of concentration and retention, in memorising the 120 cards in possession of all the players."

The origin of European playing cards is not cut-and-dried, but John Berry, the guest curator of the Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing Cards collection, has done more research than most and says: "The earliest authenticated references to playing cards in Europe date from 1377, but it seems that cards were most probably invented in China where paper was also first introduced.

"They then entered Europe thanks to the Islamic influence [the invading Moors had become card fans, after they were brought along the trade routes from China] and spread like greased lightning so that within 20 years most of mainland Europe had adopted the idea of playing cards. There were many variants to the suit and court-card systems that were to evolve in different countries. But it was the French who developed the system that we know of as hearts, clubs, diamonds and spades."

The European playing card guilds of the 17th and 18th centuries then cornered the market for producing thin card and this led to a multitude of unintended uses being found for playing cards. Miniature portraits were painted on the blank backs of playing cards because the pasteboard was considered stable. In Canada, at the end of the 17th century, a governor ran out of money and commandeered the packs from his garrisons. He wrote an amount and his signature on the blank backs, redistributed them to his soldiers, ordered more packs from France, and the system was used as valid currency for 50 years.

Collectors have found printed funeral announcements, visiting cards, invitations, contents' inventories for houses, lawyers' briefs and indexing systems, all on the back of playing cards, which were to remain plain until the middle of the last century.

Most collectors are happy to pay double figures and sometimes even three-figure sums for packs of rarer cards but they are no match for the financial resources of the public bodies. In 1983 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York paid £93,000 at Sotheby's of London for a complete set of Flemish cards from 1477. And the new French Playing Card Museum recently paid £75,000 for a single 15th century tarot card. The majority of collectors accumulate the imaginative modem packs that come on to the market. Roughly 150 new pictorial non-standard packs become available for sale every year. This figure doubles when promotional packs are taken into account.

Advertising on the backs of cards started with American tobacco manufacturers and Belgian breweries in the 1890s. Cruise liners in the Twenties and Thirties, and airlines from the Fifties onwards, gave away packs to entertain passengers on long journeys. And, more recently, they have been given to shoppers: a Bass pack came with every purchase of an eight-pack of beer, and 54 (including jokers) Brook Bond monkeys were given away with tea bags.

In Germany and Austria, political parties issue reverent pictures of their own candidates, complete with policy statements and text. In France, however, the French president's men tried to ban a cartoon pack known as "Les Giscartes" showing d'Estaing, among other things, dressed up in his wife's clothing. The packs were smuggled into Belgium and now fetch up to £35 a set.

Occasionally the 52 cards in a pack determine a theme. For centuries there were 52 shires in England and Wales and today one county card from the 1676 pack will fetch upwards of £100. Waddingtons used to give away packs with the 52 weeks of the year imprinted on the back of each card. And a Canadian company recently published a set of 50 American states, with Washington DC and Puerto Rico used to make up the numbers.

Playing-card publishers are not above producing images for titillation. Packs containing erotica have been in the public domain for centuries and ingenious means have always been used to confound the censors. Translucent packs of ordinary-looking cards were produced in the 1800s that, when held up to the light, would reveal raunchy images behind the surface print. Translucent cards are often found with burnt edges, having been singed by candles, but undamaged replica packs are available for modern collectors.

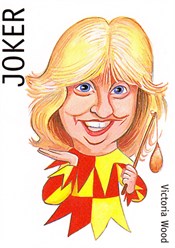

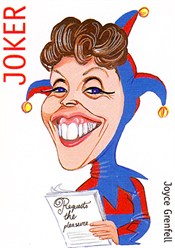

In the UK the major stockist of replica and modern cards is Roderick Sommerville in Edinburgh. It has 1,800 different packs from around the world, the majority costing £3 to £7. Most popular are the coloured drawings depicting the kings and queens of Scotland and England. Other good sellers are irreverent cartoons of the Royal Family; a deck featuring Gilbert and Sullivan characters and the recently released Woman's Hour pack portraying some of the Radio 4 programme's favourite personalities, both contemporary and historic.

Since Charles I granted a monopoly on making playing cards to trade guilds, and Cromwell promptly conducted his own crusade against frivolity and gambling, the history of playing cards in Britain has largely been one of consolidation. Although there are no large printers of cards left in the UK, the number of quality designers, and of people willing to put together interesting packs, remains high. In fact the deck is now stacked in the collectors' favour.