I wrote an article for the Independent on Sunday magazine about the shaving paraphernalia that people collect from the 1900s and before. A cut-throat business is still up on the Independent website. The original layout, with photos looked like this. Here's the whole piece:

A cut-throat business

Last year, Disraeli's old razors were sold at auction for £1,400. Shaving paraphernalia prices have tripled as interest has mushroomed. Dominique Joyeux meets the collectors who are at the cutting edge.

Renzo Jardella, Britain's most dedicated collector of safety razors, is reaching a crossroads in his life. The walls of his home are lined with display cabinets full of shaving artefacts, and many more boxes heaving with the stuff are hidden away in storage. It is time to decide what to do with his ever-expanding collection.

Renzo's would prefer to use his 30,000 quality shaving items to create a hands-on Shaving Museum of London. If he does it will be the world's only such museum, including among its attractions a working barbershop where men can experience the sensory delights of a traditional barber's shave - the hot, scented towels softening up the beard; the gliding of the cut-throat across the cheeks; the soothing face massage. Renzo feels this experience would refresh even the most jaded visitor.

He himself is a clean-shaven Londoner of Italian descent, whose trade is restoring antiques. His collecting obsession takes him around the world, buying and exchanging razors. His willingness to drive to a weekend antiques fair on spec and his early-morning habit of searching through exhibitors' displays before the crowds arrive, have turned Renzo from a keen collector to a potential curator.

"Since the age of 15, I've always collected things," he says. "If there are more than two of anything, then I've collected them. At one time I amassed the largest collection of escape and evasion items in the world. There were lapel knives, pens with guns in them, compasses in pencils and fly buttons, silk maps in jacket linings and camouflage outfits to suit every possible climate and landscape. But I couldn't really sustain two collections and a family at once, so I sold the escape and evasion equipment to the second largest collector."

The only two items he kept for himself were two unusual razors. One contained a compass, the other was like a transformer toy and changed into a dagger. These joined his main shaving collection, which tells the story of men's shaving habits around the world. His razors from Ancient Egypt - resembling small, one-bladed tomahawks - would have been used to cut or scrape the hairs off men's heads as well as their cheeks, as a way of dealing with the omnipresent lice and sand. The Romans - unlike the bearded Greeks - were also a shaving civilisation and used palm-sized, sharpened bronze blades to scrape their cheeks. After the Middle Ages, the more familiar straight razor (or "cut-throat") took over. This tool barely changed its shape during the 600 years until this century. Renzo Jardella's main interest, though, is "transitional razors" - the type which, from 1850 to 1920, created the revolution that made razors safe for the layman to use and marked the death-knoll for barbershops.

The number of razor collectors has mushroomed in the last five years, so the going rate for shaving items has doubled or tripled in price. Top- of-the-range mother-of-pearl cut-throats can change hands for pounds 300, and even bottom-of-the-range pearl razors whose handles are made up of several pieces of pearl can fetch pounds 45 to pounds 50.

Among the more sought after razors are the seven-day sets. These are straight or safety razors with a different day of the week engraved on each blade. This allowed the shaver to rest the razor for a week - which, it was claimed, gave the blade a sharper edge when it was next used. There are even 31-day sets in existence.

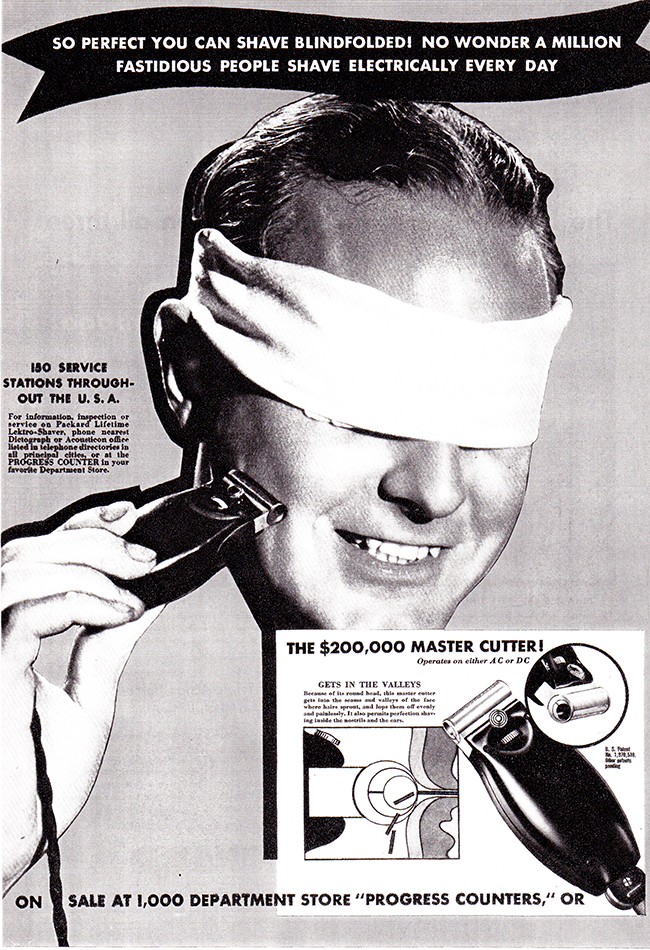

More recent electric shavers also have their ardent collectors. The first model appeared in 1931, produced by a retired American army colonel called Jacob Schick. Most of the major shaving companies followed his lead - and a few non-shaving ones too. Bofors, the gun manufacturer, tried (as did Bang and Olufson, the Danish hi-fi maker) to jump on the electric shaver bandwagon. An early Fifties electric shaver, in its box and with a decent cable will command between pounds 15 and pounds 20.

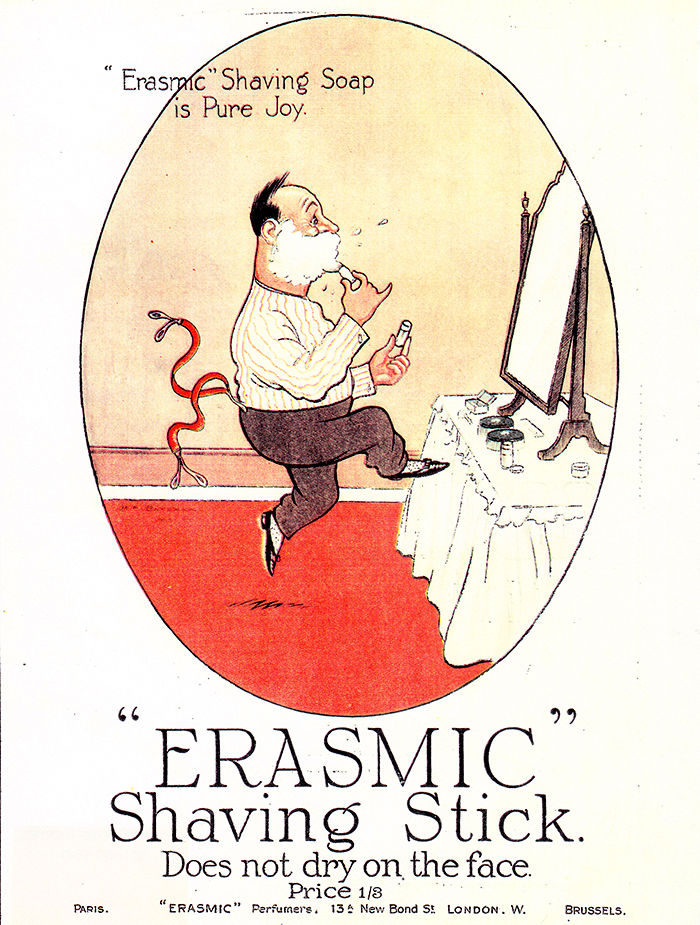

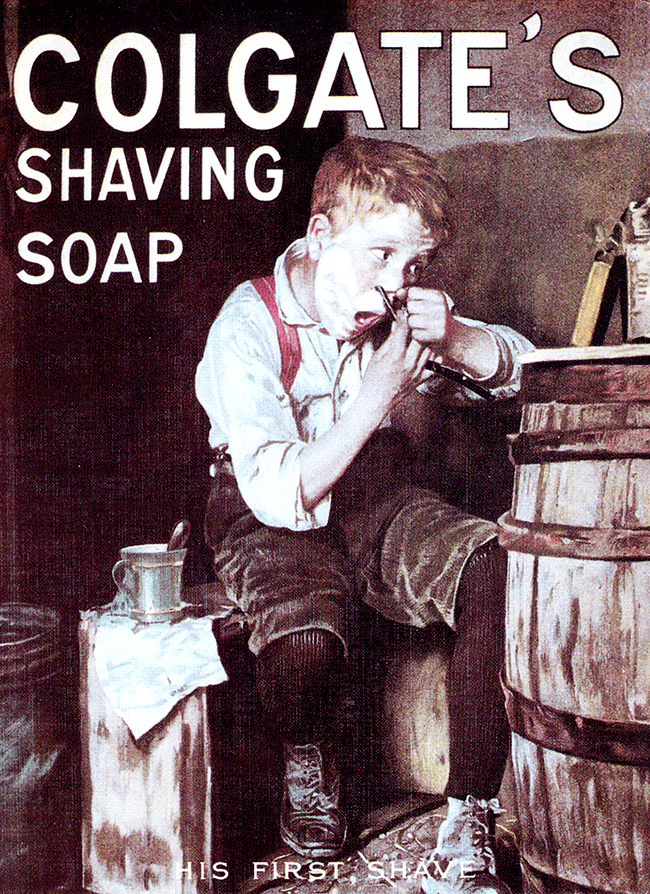

Because shaving items are made from a wide range of materials, shaving collectors often have to vie with collectors from other fields. Bakelite collectors are attracted by Thirties and Forties razor packaging; lovers of sterling silver collect straight and transitional razor blades; collectors of advertising items snap up Coca-Cola disposables and other ephemera, while those who collect gizmos and mechanical oddities are fascinated by the gyroscopic motions of pre-electric dry shavers.

Ceramic collectors are also attracted to shaving items, particularly shaving bowls of the 18th and 19th century. Oval or round shaving bowls were specially indented to fit around the client's chin and catch the lather scraped off by the barber. These are often decorated with country scenes, flowers and shaving paraphernalia. There are many copies on the market, but a genuine plain 19th-century one will cost at least pounds 55. Imported Chinese and decorated varieties from the 18th century will fetch pounds 3,000 or more.

Shaving mugs, too, are often skilfully decorated and collected in their own right. European mugs can be made of pewter, sterling silver or porcelain and have two compartments to hold the soap and the water. In America, the collecting of mugs is more esoteric - and prices reflect this. American barbers had racks running along their walls to hold clients' personalised porcelain mugs. These usually featured a design denoting the owner's trade, and today's prices highlight the respective rarity of these occupations. Horse dealers and railroad people were quite numerous at the turn of the century, and fetch only $50 apiece. A mug which belonged to an undertaker or baseball player will fetch $1,000 or more.

Despite the current boom in shaving ephemera, Renzo Jardella can still find shaving items when taking his early-morning walks around the stalls of Petticoat Lane, Portobello Road and Camden Lock. Finding straight razors made of cowhorn, bullock horn and cellulose is relatively easy, he says. What true collectors look for are good examples of razor handles made from less common materials.

Mother-of-pearl handles, for example, are hard to find in good condition. Most were made in the last century, but the pearl handles have the disadvantage of becoming slippery when wet. During two or three years of use, a man was bound to lose his grip at least once - and nobody in their right mind was going to attempt to catch a falling cut-throat

Tortoise shell razors in good condition are also a rarity, since they are susceptible to being eaten by the larvae of the carpet beetle. "I've seen some wonderful tortoise shell razors that have been devastated by being eaten right down to the blade," says Renzo. "With tortoise shell, as with ivory - which tends to dry out - it pays to massage a little almond oil into the handle from time to time."

A hundred miles north of where Renzo lives, in 200 carefully labelled albums, is one of the world's five largest collections of razor blade wrappers. Its owner, John Liss-Ronett, works with his wife from their Midlands home translating books and business texts. Like most collectors, John started filling his bedroom with collectables while still at school. "In the playground, boys were always collecting things. One month it would be fancy razor blade wrappers, the next football cards. Then we'd move on to exchanging the papers wrapping our break-time oranges. I made the decision to buy the other kids' razor wrappers when they moved on to football cards, and the dye was set."

In the 40 years since, John has traded, swapped and added to his collection so that it now stands at over 26,000 different wrappers. The pristine blades they once enveloped would keep every man on Guernsey clean-shaven for a year. Razor wrapper designers tried hard to make the manufacturer's product unique. Some, like Gillette, kept their wrappers unchanged for decades. The portrait of King Camp Gillette, with his flowing signature underneath, has remained the wrappers' trademark for 90 years. Others varied their designs, embracing popular themes such as animals, sports, ships and famous people. Among the more unusual were those given away with bottles of whisky, packets of cigarettes and the ubiquitous Coca- Cola.

Nobody knows exactly how many wrappers exist to be collected, but there has been an attempt recently to bring some kind of order into the collecting world by issuing catalogues. This is a trend John regrets. "One of the beauties about collecting blade wrappers," he says, "is that there are no definite values or known numbers of razor blades. How boring it would be if everything were to be catalogued. What fun would there be in haggling, if every wrapper already had its price?"

Shaving items that originally belonged to royalty or the famous are, in collecting terms, the equivalent of winning the National Lottery. A pearl razor that once belonged to King William IV, say, will be double the price of one with more plebeian origins. Last year at auction, a boxed gentleman's set containing pearl straight razors with gold pin work, silver mirror and mini strop fetched a handsome pounds 1,400. The reason for the inflated price was the name of its first owner - the dapper Victorian Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli.