My first ever article and Bingo! I get published in Cahiers du Cinema. Channel 4 was being born and had this wonderful ethos to kick-start British film-making. High brow at its inception I knew that it would be difficult to get an interview with its Chief Executive, Jeremy Isaacs (who would go on to head up the Royal Opera House). I got to talk to Justin Dukes, managing director of Channel 4 whose track record was in business, setting up the journal Financial Times in Germany. And I visited C4's HQ in Charlotte Street in the West End to speak with Alan Fountain, its commissioning editor for independent film in 1982.

British Film Production

As British film production and cinema audiences reach their lowest points comes the surprising prospect of a new television channel being the rejuvenating force behind a new wave of British films. Britain's fourth television channel -Channel 4 is its name- will be providing £6million in advance to twenty film projects this year and the next and if a success, the backing would increase.

British cinemas in 1982 had a lamentable year, admissions falling below a million a week for the first time since the war- when the average was 30 million. Various reasons have been proposed by cinema folk, none of them quantifiable: last year's Hollywood strike which led to a dearth of product, the recession with its 3 ½ million unemployed, the Falklands War which increased the number watching television, the bad weather, but it is rather due to the home-video explosion and a much longer and continuous trend caused by the lack of local product ie British films made by film-makers who understand the majority of Britons and who can interest them. Despite the success of Chariots of Fire only 15-20 feature-length films were produced last year.

Letter to Breznev (1985) Channel 4 production

Starting in November 1982, Channel 4 has 60 hours of programming a week. For the most part Channel 4 will be increasing the work available for video companies, but the opportunity for film-makers comes in that the fourth channel sees itself as a publisher rather than a programmer or an originator. As a publisher they take individual offers of writers who are 'auteurs' and commission them to make individual projects. This financial year (until next March) they've commissioned 20 films to be made by independent directors giving £300,000 to each one. The main proviso being that Channel 4 be allowed to screen the film while it is still 'hot', this would probably mean three to six months after its cinema release date instead of the present two to five years.

Channel 4 thus doubles the amount of films coming out of Britain and in an indirect way could produce more. For a further £700,000 is being given to 17 independent film workshops this year to buy editing equipment and cameras. In return Channel 4 expect to see an increase in quality and quantity of independent low-budget films. Enough to fill in a two hour programme once a week that features films made by non-professionals.

This has been achieved with the cooperation and a fresh outlook from the film unions. The unions have gone out of their way to allow workshop-produced films to be shown on television without union members among them and they are probably unique among the unions of the world in allowing this.

Channel 4 is going to be producing some fairly obscure pieces and indeed do not expect to get more than 10% of the television public, but they are using this channel to experiment. It is taking up a lot of work that would not previously have been shown on other channels.

The managing-director of Channel 4, Justin Dukes explains his vision of how to put across 'alternative' films and how cinema and television can be complementary instead of competitive.

"The task is to persuade the television audience that cinema isn't only a diet of James Bond but that it's something that is capable of looking into issues and is enjoyable. That there is a dimension there that they go and experience. For example it is quite impossible for television to do justice to The Draughtsman's Contract (one of the first films completed with the aid of Channel 4 money). With all its detail, its subtleties a lot of the attractions of this film are going to be lost on the small screen.

"The very first thing that we've got to do is tell the audience to take the phone off the hook, put the children to bed or tell them to keep quiet, disconnect the doorbell and watch this film. You will not get more than 40% of what it has to say if you watch it like Benny Hill. Even with the above precautions I don't think we'll have people getting more than 60% out of a film when it's shown on TV. So what I hope will happen, is that at the end of the film we'll be able to say that this film is on at the following cinemas. Because television is a tremendous scattergun and I hope we can change people's conception of television and cinema. The idea is not to further damage film or cinema but in fact to develop a new chemistry of the relationships between different media."

My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) Channel 4 production

What Justin Dukes is graphically alluding to is a marked difference in tastes that exists between the minority who will regularly switch on to Channel 4 and the majority who will treat the new channel with caution. There exists in Britain a kind of 'culture-gap' though not as marked as in the United States, the gap is growing between those that regularly go to the theatre, art houses and alternative cinemas and those that will only go to the cinema to see a film that has been heavily advertised, the content of which is pretty well-known beforehand

The choice of which film to watch becomes ever more crucial in a financial world where for a family of four it cost 10 to 15 pounds to go to the cinema, compared to one pound to hire a feature-film on video for the night. Over two million video-cassette recorders have been sold in the last two years and the video 'pirates' have become independent distributors themselves. For example E.T. has been available under-the-counter since August and the film is not due for release until Christmas.

Phyllis Logan (of Downton Abbey) in her first film Another Time Another Place (1983) - Channel 4 production

A major British film producer complains that only about 15% of the tapes on the market are non-pirate.

The British film industry has never been a healthy one, for the most part relying heavily on American finance. It has basically been a problem of risk-capital and the dependence on investors. Investors in Britain have been discouraged by producers who produce films that consistently lose money. Investors themselves are very conservative preferring to invest in South Africa rather than in unpredictable films. In United States they are more gamblers and risk-takers and willing to take a chance in films. Channel 4 is a forward step. Cable television will also produce more money for programmes when it is ready. There are already a few towns in Britain that have started laying cables, however it will cost £5,000 million pounds to reach just two-thirds of the homes here. So it will be at least a decade before cable television influences project-creating significantly.

"What is needed is a whole new investment climate" says Steve Bernstein, a US film maker. "If the government made investment in films more attractive like making films tax-deductable like they did in Australia and Canada. Then like Australia and Canada a whole new film industry could develop overnight. It wasn't that the film industry was there and suddenly they allowed people investing in it and then started producing creative masterpieces. It was quite the other way around in that first they allowed the tax-relief for investment and then they discovered that they had this native independent film talent that could produce good film."

If that happened in Britain, then there are already the cinematographers, enough directors, accomplished actors and actresses, in fact there is very little missing. This has been demonstrated by Channel 4 already. They have had a thousand scripts sent to them for the first 20 commissioned films. Even if only a tenth of these scripts were of quality and could be produced, then the forever-echoing Truffaut taunt that English Cinema is a contradiction in terms, would become an historical joke.

© Dominique Joyeux

A full list of Channel 4's film output is available here, 300 films and counting…

Postscript: The thing that tickles

most, looking back on something I wrote 30 years ago, is the

slowness and complexity involved in creating these articles. There

was no internet, there was no Wikipedia. When I say I did research,

I mean that I went to the local library, looked through yellow

pages, phoned up umpteen secretaries trying to get background

information until I finally found the person that I thought would

be able to give me information and who would be important enough

for foreign magazines to recognise.

Postscript: The thing that tickles

most, looking back on something I wrote 30 years ago, is the

slowness and complexity involved in creating these articles. There

was no internet, there was no Wikipedia. When I say I did research,

I mean that I went to the local library, looked through yellow

pages, phoned up umpteen secretaries trying to get background

information until I finally found the person that I thought would

be able to give me information and who would be important enough

for foreign magazines to recognise.

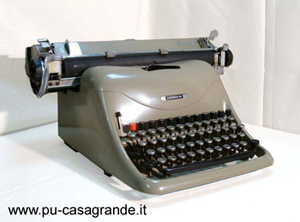

And then having recorded the interview on a Sony

Walkman 'Journalist' cassette tape recorder I would handwrite the

transcript and then the article. And only when I was nearly sure

that it was ready would I type it up using my mother's extremely

heavy 'Fifties Olivetti Lexicon 8 typewriter (pictured). I would

then type with one finger either hand (like I am writing now) and

try not to hit the strokes too hard. Bashing the metal rods into

the fragile typing paper meant creating holes in the 'a' and 'e'

characters (see alongside). A certain amount of force was needed

though to get through to the carbon paper which would then cast a

copy of the letter onto the paper behind. Photocopying machines

were pretty naff and few and far between in those days and so it

was best to make a copy at home to send to the magazine.

And then having recorded the interview on a Sony

Walkman 'Journalist' cassette tape recorder I would handwrite the

transcript and then the article. And only when I was nearly sure

that it was ready would I type it up using my mother's extremely

heavy 'Fifties Olivetti Lexicon 8 typewriter (pictured). I would

then type with one finger either hand (like I am writing now) and

try not to hit the strokes too hard. Bashing the metal rods into

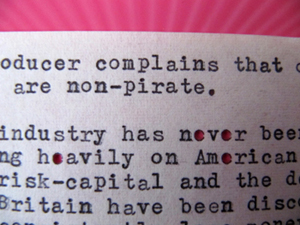

the fragile typing paper meant creating holes in the 'a' and 'e'

characters (see alongside). A certain amount of force was needed

though to get through to the carbon paper which would then cast a

copy of the letter onto the paper behind. Photocopying machines

were pretty naff and few and far between in those days and so it

was best to make a copy at home to send to the magazine.

Hitting the wrong key and thus the wrong

letter was not so serious. That was what Tipp-Ex

was invented for. As long as you spotted the mistake straight

away, painted on the Tipp-Ex, waited a minute for it to dry and

then rehit the right letter it wasn't too bad. But if you only

noticed after you had taken the paper out of the machine you were

buggered and would never be able to line up the paper in the right

place again. Then you would probably give up, cross the letter/word

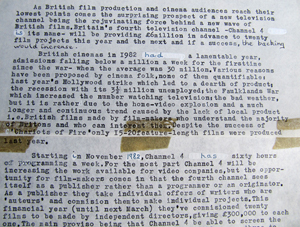

out with a pen and write the proper word above/beside it. Alongside

is the beginning of this article.

Hitting the wrong key and thus the wrong

letter was not so serious. That was what Tipp-Ex

was invented for. As long as you spotted the mistake straight

away, painted on the Tipp-Ex, waited a minute for it to dry and

then rehit the right letter it wasn't too bad. But if you only

noticed after you had taken the paper out of the machine you were

buggered and would never be able to line up the paper in the right

place again. Then you would probably give up, cross the letter/word

out with a pen and write the proper word above/beside it. Alongside

is the beginning of this article.

Published in:

Cahiers du Cinema - Decembre 1982.

Cahiers du Cinema - Decembre 1982.

Chaplin nr6 1982.

Chaplin nr6 1982.