At one point I was regularly sending items to Cahiers du Cinema from London. This one was about the opening of the Museum of the Moving Image (MOMI). I interviewed the driving forces behind it, Leslie Hardcastle and David Francis, in the Summer of 1988 for the October issue of Cahiers.

London's Momi

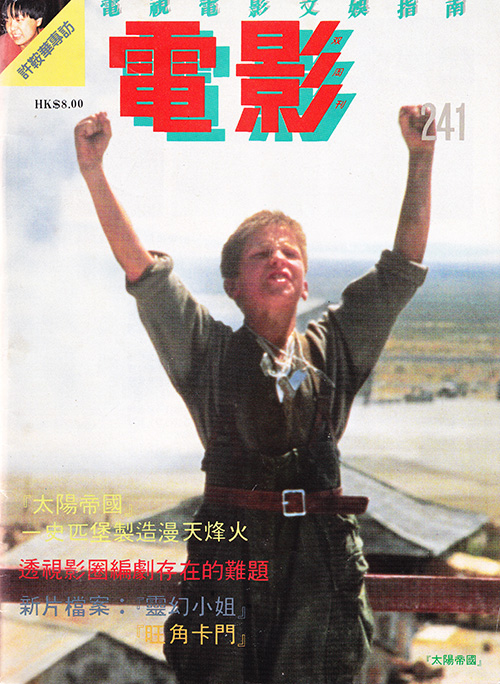

This Autumn's London cinematic event is undoubtedly the opening of MOMI, museum of the moving image, inaugurated on September 15 by Prince Charles in person.

The presence of a celebrity at an inauguration can be an advantage, but sometimes a disadvantage. The advantage for MOMI of Prince Charles inaugurating the museum, was the presence of foreign journalists, television outlets, and printed features in all the British daily newspapers the next day. The downside was that the Prince, (as patron of the British Film Institute), decided to take the opportunity to comment on the 'relentless parade of absolutely gratuitous violence' that can be seen on television and cinema screens. These reflections by Prince Charles align with what many parents of his generation think, but his speech irritated the majority of directors present at the inauguration. They wondered if the words of Prince Charles were intended for them.

Waterloo Bridge acts as the roof for MOMI © Alamy

The opening of MOMI was the high point of the year for British audiovisual professionals. It created the possibility of a pilgrimage to this new Mecca of their industry. The most notable absence at the launch was that of John Paul Getty Jr, the Museum's reticent chief fundraiser. MOMI's first visitors were perhaps over-enthusiastic, but they seemed to agree that it was 'Europe's most exciting museum'.

It is certainly the first time that a national museum has been built in this century in England without government assistance. The entire project has been entirely financed with private funds, and will continue to run on its own resources.

The MOMI concept was dreamt up by Leslie Hardcastle (National Film Theater director) and developed by David Francis (National Film Archives curator). It cost £7 million. It is a three-storey roofless building, housed under London's Waterloo Bridge, on the south bank of the River Thames.

Treasures from the Archives

It may be surprising that a film museum hadn't been built in England before 1988, considering that the National Film Archives has long boasted of having the largest collection in the world. With approximately 4 million black-and-white photos, 400,000 colour, and 80,000 feature films, the National Film Archives has long been the most important provider of major film exhibits, and an incomparable research centre.

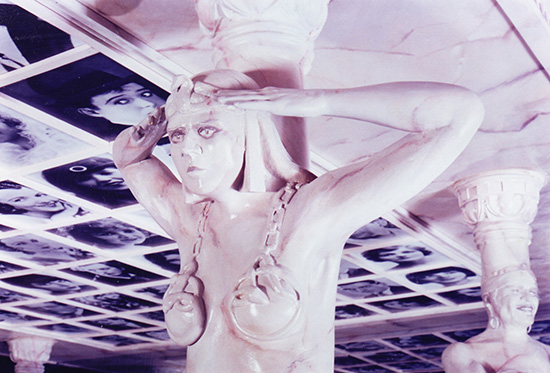

Theda Bara supports the 6 metre Graeco-Roman temple to the Gods (MOMI)

The Archives has also undertaken to restore, by the year 2000, some 50 million metres of deteriorating nitrate film. By copying them onto film, as well providing storage space for 500,000 reels of 35mm film in an adequate environment.

This large stock of films has come from various sources. On one occasion, a television company that had lost its airtime rights, left its films on the pavement, calling the Archives to come and collect them. Another lot had to be fully restored after being left in a henhouse, and there are also some old reels salvaged from the RMS Lusitania, the liner torpedoed during the First World War.

The archive also has a collection of film memorabilia that will provide a foundation from which MOMI can grow: sets, including those for Black Narcissus, Red Shoes, and several Hitchcock films; a huge collection of posters - including those of all the Ealing comedies; letters from Sergei Eisenstein and Satyajit Ray; Conradt Veidt's naturalisation papers dated February 24, 1939; Errol Flynn's costumes for The Sea Hawk (L'Aigle des Mers); Fred Astaire's tailcoat and pants, and lots more. A large number of small handmade objects by Akira Kurosawa, and private collections such as that of Sir Michael Balcon and that of the British Board of Censors. MOMI will continue with acquisitions, and has already bought Charlie Chaplin's hat and cane from Christie's for £15,000, as well as a lot of early cinema equipment.

The 'godfathers'

The funds to build the MOMI were raised thanks to important donations from people like Robert Stigwood, Sir Yue-Kong Pau, and from the most generous millionaire cinephile living in England, J. Paul Getty Jr. He had already financed several English films, as well as the buildings of the British Film Institute. Getty has a collection of small B films - a passion dating from his youth and owes much to his mother, Anna Rourke, who starred in six films, and his father, then owner of a studio.

"The MOMI has 43 main exhibition spaces," says David Francis OBE, "of which an eighth is convertible, so that over the months we can change the Museum, so that it is never the same on each visit. It's always a new experience. It was never intended to make a visit to the Museum a history lesson, but to choose a range of subjects that together cover the history of cinema."

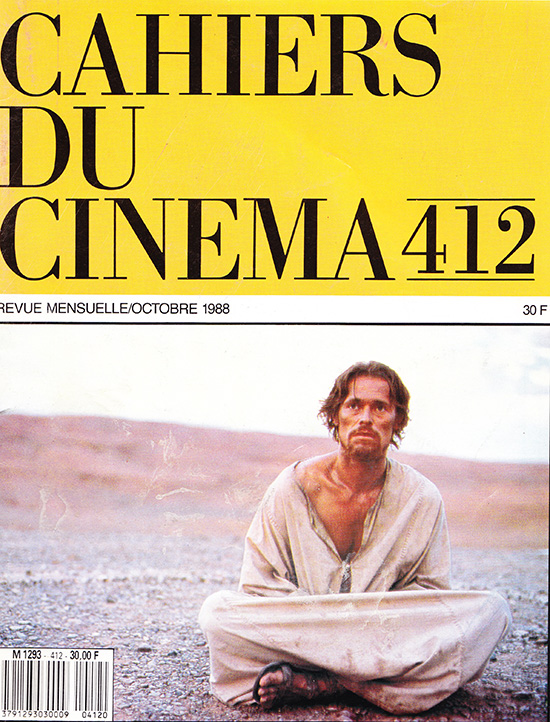

Centre-page spread for Cahiers du Cinema 412

"The arrival of sound, cinema as a big industry, youth culture, the political force of television, the development of cinema as an art form, the history of the two technologies of cinema and television, and of their bond, a study of advertising, and many other aspects of cinema. We would like to see it as a mixture of a cinematic time machine with the magical essence of Arabian nights."

Touch the cinema

Leslie Hardcastle OBE, who conceived and helped develop MOMI, continues: "It will be a museum where people can touch, visitors can press buttons, operate cameras, edit films, ride a Russian agit-prop train, talk to actors playing different roles, have an overview of new techniques. This will allow passers-by to acquire a little cinematic language.

"Certain sectors of the exhibition take the form of 'Drive in' cinemas, a Hollywood sidewalk of celebrities, a Parisian macadam with excerpts from famous films. You might see people fixing projectors, shooting sequences in a decoration department, filming special effects, or putting on a magic lantern show.

"Because we are not allowed to have more than a thousand people in the Museum at a time, there will be a queue outside, but they will be the most fun queues in London. They can sit on benches covered with questions about the cinema. TV shows will be shown on the way, and children can play with cartoon toys. We will also break an unwritten rule of museums, which is that they are closed in the evening. We will let visitors in after 6:30 p.m., we will close around 10:30 p.m.

"To balance its expenses, it will be necessary that almost half a million people come to visit it. The price will be that of the cinema ticket at the nearby National Film Theatre, that is to say around £3. If MOMI is as successful as the recently opened National Museum of Photography in Bradford, which now welcomes over 700,000 people a year, then Prince Charles, Richard Attenborough, and the other distinguished members of the MOMI Board of Trustees will be proud to have bet on this 'cinematographic time machine'"

Postscript. Unfortunately MOMI was short-lived and closed in 1999. The UK currently has no national cinema museum and so many of its treasures remain unseen. There is a London Cinema Museum which gets good reviews, and in 2018, David Francis established the Kent MOMI in Deal.

|

|

|