This interview was conducted in central London starting off at David Puttnam's office. It was at the end of a working day and he put the office phones on voicemail so that he could focus on our talk. We overran though and he was due to be at a BFI meeting a couple of miles away so we continued our chat in his small car with me in the passenger seat. Here was Britain's biggest film hitter of the time and I was holding my Sony Walkman recorder close enough to his face trying to capture his voice above the sound of the motor. Cool!

David Puttnam

Born in 1941, in London, as the son of a photographer, David Puttnam enjoyed a successful career in advertising before his entry into cinema. The success of films like Bugsy Malone (1976), The Duellists (1977), Midnight Express (1978), Chariots of Fire (1981), Local Hero (1983), and Cal (1984) and his ability to develop cinema directors more accustomed to working commercials and television, have gained a respect for him from both the worlds of business and artistic cinema.

David Puttnam - 1985

Jonathan Benson, assistant director of Chariots of Fire and Local Hero, says of him: "David has a more human attitude than any other producer I know. He covers every aspect and is clued up on all of them. He doesn't show this side but he loves a confrontation, a fight or a struggle - it taxes him a bit. There is an immense loyalty and a family atmosphere in his films. He's not high up but accessible to everyone and makes one feel like an exceptionally important person to the making of a film. He has a tentacle in all known pies but I don't think he personally makes a lot of money from his films. He is the only producer I know who gives a percentage of the film profits to all the crew (for Chariots of Fire this returned a minimum £1,500 share for each crew member) and he won the Oscar, but it belongs to all of us."

David Puttnam has just finished producing a series of one-hour films for Channel 4 called First Love. He lectures worldwide at film seminars and is a governor at the National Film and Television School. It is at the School that he sees his future after his producing engagements became scarce - teaching students and encouraging youngsters in the film business.

Dominique Joyeux interviewed David Puttnam on the first day of 1985 as he and others were preparing to launch Britain's own Year Of the Film, where it is hoped that his own contributions Cal and The Killing Fields will help stimulate an otherwise lethargic film-going public…

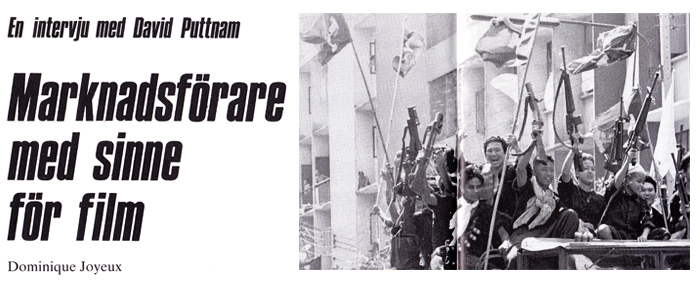

The actual cost of The Killing Fields was £10 million, more than half of which was made up of American money. Its cameraman, director and producer were British. Would you call The Killing Fields an American or British film?

Sam Waterson and Dr Haing Ngor

I think The Killing Fields, because of the manner in which it addresses its audience, must ostensibly be looked at as an American film. I think in the manner of its manufacturing process, that is, in the nature of the way it was conceived, I would say that it was a European film, not a British one. It was conceived in a European manner, but addresses its audience in an American manner. It is not the first film to have done that. A couple of Louis Malle's films have also followed this pattern.

I see myself as a European film-maker, I am definitely not an American film-maker. I do not understand the American film-making process. It is alien to me. I tried it once and I failed at it.

In what way did your experience in the advertising business prepare you for making films?

Brilliantly. It is an interesting point. If I had gone straight into the film industry, as I wanted to do, my career curve would have been quite a different one. It's arguable as to whether I would ever have been a film producer at all, and if I had, it would have been a film producer with a different set of skills.

When I came out of advertising, I virtually fell into the job of producer without realising. Today, I still think of myself as a marketing man who happens to produce movies, not as a film-maker who happened to have an advertising background.

A lot of people make the mistake of lumping advertising people together and calling them crass and tasteless. In fact, the advertising industry itself has more wisdom about people's tastes, about what motivates and moves them, than perhaps any other public sector. The resources available to them, in terms of listening to the public through surveys, polls and customer research, are greater than any other business enterprise.

I learned - at a point in my life where it was not offensive to learn - that the key to having a successful product was in tailoring the product to a market. The fact has never been repugnant to me. I do think, however, that to a lot of colleagues in my business, it is a repugnant thought. They were film-makers from an early age and the idea of addressing a film to a market-place was distasteful. I think most of them enjoy seeing a queue outside a cinema, but the idea of their film having been tailored for that queue is an ugly one.

Me, when I read the original story of The Killing Fields, or when I read the original notion of Bugsy Malone, or Chariots of Fire, I read them, if you like, as products. I thought: Here is something that if properly crafted could fit into a gap which I think exists in the cinema-going market. There is no point in apologising for that thought because it is definitely the way my mental process works.

Your job is to turn dreams into reality. Do you ever get scared that the dream will turn into an expensive nightmare?

Scared, no. Concerned, yes! Until a few months ago I would have said a definite no but now it is less of a no.

I am very proud of The Killing Fields but it took a lot out of me. In completing the mammoth task of preparing and finishing this film, I feel like someone who has just jumped across a chasm; gone back to the edge of that chasm and checked how far down he would have fallen had he not managed to jump far enough.

That has frightened the life out of me. I don't for one moment ever think I realised what a gamble I was taking with The Killing Fields. If that sounds self-congratulatory, I don't mean it that way. What I really mean is that I will be forced to assess more seriously what I am letting myself in for in the future and to acknowledge the possibility that I will become more fearful. It is one of the things I'm worrying about at the moment, one of the things I am having to cope with.

Would you ever put your own money into a film again?

No. Not because I don't think that it is a good idea but I think it is liable to encourage you as a producer to make the wrong judgements. I wouldn't want to be at dinner with a director, discussing the following day's work and calculating the number of extras that we need, knowing in my heart of hearts that if I were to get away with a hundred less I would be saving myself some money: I think that's the wrong equation to be applying.

Casting Dr Haing Ngor, a doctor, not an actor, was a big risk to take on a multi-million dollar production. How and why did you take this chance with an unknown?

To be honest, it was a question of necessity being the mother of invention. Just about all the Cambodian actors were killed. They were one of the first groups of people to die in the Khmer Rouge revolution. We were not in the position of having a large choice among Cambodian actors.

We had some choice among the Chinese actors but we decided to try and get the nearest to the reality that we could and out of the trawling process of seeing every Cambodian that might be right, came Haing, six weeks before we were due to start principal photography. We had a back-up man who did not know that he was needed, but we made sure that he was available in case something happened to Haing.

Do you think he deserves an Oscar for playing that role?

Dr Haing Ngor as Dith Pran

Yes and no. I would like to see him get an Oscar as Best Supporting Actor, not as Best Actor. This is because I see the craft of acting as a very specific one and one that I admire very much. The great skill of an actor is not the days that he gets it right nor even the films that he may get it right in. It's his ability to pull a performance out of adverse circumstances. It is then that the actor comes through, when everything else is going wrong.

Acting is a very special craft, that owes a lot to experience and a lot to training. I think it's wrong to give the impression to the public th at anyone can act. I happen to believe that anyone can act, but that anyone can act in one role and at one time. You and I could perform marvellously given the right director and the right role. We would not perform well, however, if we were asked to play Prospero on a wet Thursday in Folkestone, but that is acting. It would be a wrong evaluation if Haing won the Best Actor Award and not be fair on other actors. (BTW Dr Haing Ngor did indeed win Best Supporting Actor)

What response have you had from the Americans towards The Killing Fields?

Very favourable. Only three newspapers I have read so far have described the film as being anti-American and they were all three British. Not one single American paper has criticised the film in that respect. There were some who were sceptical, one or two even scathing about the picture, but none who thought like some British that it was an anti-American picture.

What do you think that says of the British Press or even of the American Press?

America is such a confident nation at the moment that they are able to absorb criticism in a way that we in Europe find impossible. They just don't have our form of political sensitivity. In getting rid of Nixon they really did purge themselves in their own mind. I have watched it with a dozen American audiences now, and there is a gasp when Nixon says what he says in the film. But the United States got rid of him in the end and so Americans now feel in control.

When are big stars worth the high price they charge to act?

I have used big stars very occasionally. Burt Lancaster certainly was a very good example when the price that we ended up getting from television paid for Burt about three times over and justified his hiring. We certainly would have had enormous problems selling that film to television if it had not been for him.

Another time an actor is worth the high price is when he is unique, but I think there are not more than four or five unique actors in the world. If you want to work with them, they are worth every penny they get, because they are unique.

Local Hero was screened to a randomly collected street audience before it was released. That is an old American practice that producers use. Why is that tradition carried on?

I did it with The Killing Fields as well. I did it because I believe in it completely. I don't believe in it in terms of telling you what film to make, I don't believe in it telling you how to make it (as is sometimes done in America) but I do believe in it telling you what reaction your cut of that film is having.

I think it is the greatest arrogance to assume that the filmmaker is so all-knowing about the effects of his work that there aren't improvements that he can make. We discovered a great deal about the audience's comprehension of it.

There is an old saying that goes: "Don't confuse me with the facts". We found that the first cut of the film which we were entirely satisfied with was not appreciated in the same way by the audience. The audience had a terrific problem because in the first third of that bit there were too many facts. They were so bewildered by these facts that we changed it and discovered that the more elliptical we made it the more the audience seemed to understand. Whether they did understand it more or not is neither here nor there - they were more comfortable. When the audience is not comfortable, you can feel it, you can feel them get edgy.

That's interesting because one of the two main criticisms of the film from The Times was: "The audience may well be at a loss to understand the facts of the origins and terrorism of the Khmer Rouge".

Poster of The Killing Fields

Well, I think that is an intellectual criticism. On an emotive level they were more at a loss when we were more specific about the background to everything. I'm glad you asked me that because that is a very good example of what we learned. We didn't know it when we originally cut the film. We learnt it from a preview.

The strongest criticism from the critics who have reviewed the film in England is in the "over-emphatic" musical effects like Puccini's Nessun Dorma chorale accompanying the evacuation from Phnom Penh. They also criticised the use of John Lennon's Imagine over the final images of the Cambodian victims which represents the three million Cambodians dead and millions homeless. Whose choice was the music and do you feel these criticisms valid?

No, I don't think they are valid. The choice of music was all ours - Jim Clark, Roland Joffe and mine. It was a consensus view that we use Imagine and Nessum Dorma. It comes back to that question as to what sort of a producer I am. I work from my instincts. If I sit with a director and we watch a cut of a film, then we lay some music up against it and the hair on the back of my neck stands on end and we feel that something's working. I don't question it. As long you know that the ethical basis on which you are using it is sound - or feel that it is - then I think it pointless analysing your decision. I do not feel that people's appreciation of music can be undertaken as some kind of academic exercise. You can analyse the music of The Beatles but it would be difficult to say why people tap their feet, nod their heads and appreciate that music.

Imagine very simply worked. We previewed The Killing Fields with it, we previewed The Killing Fields without it, and the former worked.

You have said that Chariots of Fire was a film in which style covered content and that Local Hero was a film where the style was soaked up by the content. Where do you place The Killing Fields and which in the final reckoning do you prefer to see in film?

I think that The Killing Fields is packed with content and that the style grew out of it. The style was deliberately selected, the film that we modelled it on was The Battle of Algiers. I was over the moon at Christmas, when I received a complimentary letter about our film from the makers of The Battle of Algiers. It is a letter that I value and treasure.

I do not think that the style or the content of a film is more important than the other. What is so wonderful about the world of cinema is that each film is an entity in itself.

My influences as a child were two-fold and there was no way that I could differentiate between the importance of 'content-full' cinema of Kezan, Zimmerman, Robert Rosen, those American black-and-white movies of the early 'Fifties, and my equal fascination for the musicals of the same period. If I had to pick out of the multitude of the 'Fifties film artists whose films I saw as a child, the most important would be Elia Kezan and Gene Kelly. It would be fatuous for me to pretend that one was more important than the other.

Wading through the killing fields

I feel that cinema is going through a crisis at the moment in Europe and one of the reasons that we are going through this crisis is that we have forgotten completely the processes and responsibilities for developing an audience. Audiences do not appear out of the ether. No one, not one reader of a specialist film magazine, went to see Citizen Kane as his or her first movie. Their love of cinema, like my love of cinema, developed through a process.

My first film was Pinocchio and I think that the Disney films were a lot of people's first film. Where are these types of films? Where is the developmental process that allows a young audience to fall in love with the cinema and then allow that love affair to flourish to a point where it is able to really enjoy Les Enfants du Paradis. No child at the age of eight or nine is going to go to Les Enfants du Paradis and regard it as anything but a very strange experience without this developmental process.

If the best way of developing an audience is to emphasise style over content in the area of some subject matter, then that's the way you should go. Conversely, in other areas of subject matter, of course content must dominate. For me, it is an individual decision that each film must make for itself.

Who is your hero? Who is the person you most admire in the world of cinema or without?

Who is my hero? Probably as you get older, more and more of your heroes turn out to be not the ideal you once pictured them to be not the ideal you once pictured them to be. I have a lot of time for Fred Zimmerman. I think that he is remarkable, decent man and a really fine director. I wouldn't say that he is my hero but he is a figure who represents heroic values.

Diaghelev is a hero for me; for what he was and what he achieved in his lifetime. I admire him particularly for the fact that he reconstituted the Ballet Russe three times in total. That I think is sensational. It's an achievement to put something together once, but to have it collapse around you for a variety of reasons and put the whole show together twice is quite remarkable. He would be my hero, but that is on condition of my never having met him. I would probably have found him to be loathsome if I had done!

© Dominique Joyeux

Postscript: I asked to talk to David Puttnam (now Baron Puttnam of Queensgate) after seeing the film The Killing Fields in a near-empty cinema in Charing Cross Road. It is a hugely emotive movie and superbly filmed - Chris Menges got Best Cinematographer Oscar for it and Roland Joffe nearly got Best Director. At the end of the matinee performance I could hear someone crying behind me so I looked around and there was an old chap without a hankie, sobbing into his hands, simply overwhelmed by the movie.

I asked if he wanted a coffee and we went to a cafe nearby and talked about the picture. He was a real Londoner and the film had brought back a lot of his Blitz experiences. This was one of those great films that made strong moral points, engaged its audience and made strangers talk to each other!

Check out this site for a nice summary of the film and the trailer.

And there's a comprehensive obituary of Dith Pran here.

This article was published in:

Chaplin nr2 1985.

Chaplin nr2 1985.

Screen, India - 25 April 1986.

Screen, India - 25 April 1986.